Sure it’s violent but that’s why we love it. Violent, violent, violent!

It is the dreaded year 2000. The world has seemingly recovered from the epic collapse of 1979. Thankfully, there is no threat of Y2K and there is no tech bubble but Limp Bizkit is probably (okay, just look at this place—it is actually likely) very popular. And within the circular skyscrapers and endless (and still fruitful) countryside, there is a religious-like cult posing as government, with a President represented by berobed deacons across the great land.

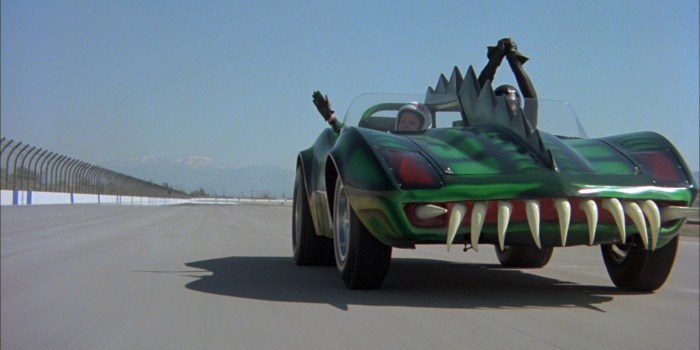

Nazism is a social trend, celebrated and marketed. Cults of personality rule the populace, some choosing to die for their chosen avatar. And Death itself becomes a set of options, like on a menu: some die so the others may live. For the Transcontinental Road Race is as American as apple pie was (before the crash, anyway). The drivers drive, maim, kill, and savage the roadways of the country for the benefit of the people. Such is the world of Death Race 2000, our first of two features of vehicular manslaughter made celluloid.

Released in 1975, Death Race 2000 is the picture-perfect example of a Roger Corman produced film: ambition defeated only by budget. For Death Race 2000 is a future dystopian vision that pretty much looks just like 1975, give or take a poorly placed matte painting here and a “futuristic” looking prop there. And, of course, the clothes—when the actors choose to wear them, that is! For the film utilizes its R rating effectively: naked women getting in catfights? Check. Heads run over by tires? Check. People impaled by gigantic knives placed on the front hood of a car? You got it.

Annie Paine: I don’t want you to die.

Frankenstein: It’s my life’s work.

Death Race 2000 is led by the charismatic David Carradine, who plays legendary TRR driver Frankenstein, a man so dedicated to the race that he’s lost multiple appendages and had complete facial reconstruction surgery. Though his face actually looks fine, he wears a mask showing a grotesque eye nearly falling out of its socket, a shattered and roadworn cheek, and a mangled mouth that will not close. He drives for the people and he drives for the win.

“Is winning all you care about,” Frankenstein’s current navigator Annie asks him. Without hesitation, Frankenstein says, “Yes. It is the only standard of excellence left.” And the people of the world won’t argue with him. This is a world that doesn’t need or want saving. Though there is a resistance group who opposes the race and wants the President dead, the population at large adores the bloodlust of the charismatic drivers. Not only is Frankenstein a celebrity, but so is Joe “Machine Gun” Viterbo (Sylvester Stallone), “Calamity Jane” Kelly (Mary Woronov), and “Matilda the Hun” (Roberta Collins), the other sadistic drivers in town.

And while Frankenstein himself might also have a hidden political stand to make, he isn’t a squeaky clean hero. In a world where bonus points are given to racers who hit pedestrians, including extra points for babies and the elderly, Frankenstein will revolt by killing the evil hospital workers who place older people out on the road for “euthanasia day” during the televised race. Sure, those nurses deserved it but he still gets a few hundred points.

Like many dystopian films of the ’70s, Death Race 2000 is laced with social commentary (just as the writers and producers were likely laced with cocaine). Because it wasn’t prophetic at all that we’d live in a world, someday, where torment was people’s entertainment and the idea of celebrity would overcome experience in the realm of leadership and diplomacy and everyday life would function as a reality show. Hogwash. Not possible.

Once again, the world doesn’t seem to want saving in 1975, 2000, or 2020.

I’m scared, Fifi. You know why? It’s that rat circus out there, I’m beginning to enjoy it. Look, any longer out on that road and I’m one of them, ya know? A terminal crazy, except I’ve got a bronze badge that says I’m one of the good guys.

It is the dreaded year 1985 (or so). The world doesn’t really seem that bad, does it? When viewing the original Mad Max in comparison not just to its immediate sequels but the soft reboot-like Best Picture nominee Mad Max: Fury Road in 2015, one forgets that it all started in a world that is only partially collapsed. It feels more like a human-based dystopia as opposed to a societally based one: there are still a police department, courts, power, gas, and plenty of restaurants. Everything looks a bit downtrodden but the biggest issue seems to be gang warfare with the highways becoming battlegrounds and territory to fight over. So, like Los Angeles today.

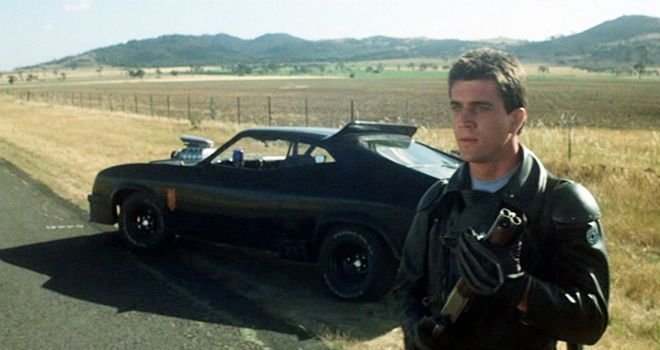

The OG Mad Max takes place in Australia (or, if you are watching the dubbed version, it could be America but you wouldn’t do that because to watch this dubbed is to be a sick human being) where a ruthless gang of motorcycle “Nomads” is running wild on the freeways, giving the Main Force Patrol a headache. When MFP officer Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson) kills gang member and out of control hyper beast Nightrider and, separately, apprehends Johnny the Boy, another nomad, from a vandalism/rape situation, the gang’s leader, Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne), makes it his priority to ruin Max’s life. Toecutter first targets his partner Goose (Steve Bisley), then his wife Jessie (Joanne Samuel) and their child.

The main inspiration, according to Wikipedia (grain of salt) and The Courier-Mail (less salt needed but link no longer available), was the Oil Embargo of 1973, where Australian citizens, amongst other nations, suffered out-of-character violence “to ensure mobility.” Much like Fury Road’s refreshing approach to women’s rights, the original Mad Max was subtly centered around environmentalism and greed. Though, in the end, the film was mostly a pretty righteous way to show bone-rattling stunts and that age-old classic: revenge.

Since Fury Road is a masterpiece and a fairly recent one at that, many might find the original Mad Max to be rather quaint. It is true that it takes nearly one full hour before the revenge plot kicks into high gear (this is more a Mad Max origin story with a cameo by the titular hero than a film fully about him). But the reason Fury Road and the original film succeed is because of their dedication to practical stuntwork. The first and last half hour of Mad Max is just as entertaining and pulse-pounding as Fury Road mostly because what we are seeing is real.

But you can’t sell a good revenge tale without the hero suffering a worthy loss, and director George Miller does an excellent job of making Jessie a fully realized character, whose death comes as something of heartbreak rather than plot convenience. In fact, just like in Fury Road, Max himself almost takes a backseat to the realization of not only Jessie but Max’s partner Goose. Both are more emotionally open and honest while Max is a rudimentary hero: the strong and silent type. Gibson’s intensity serves him well, making us care for him even though we know less about him.

Regardless of the intent behind the scenes, what comes in front of you on-screen is bold and inventive, exciting and addicting: a true gem of dystopian fiction.

*Once again, please do not watch the version of Mad Max with Mel Gibson, or anyone else, dubbed. That’s just wrong.

The social commentary may not be as on-the-nose in Mad Max as it is in Death Race 2000, but with this double feature you get the full spectrum of the fragile human condition mixed with enough vehicular mayhem to make you scared to get in your car again. Death Race 2000 and Mad Max are some of the best dystopian films you can ask for. Watch them together!

Both Death Race 2000 and Mad Max are available as part of the “’70s Sci-fi” collection on the Criterion Channel. Also available wherever digital or physical media is sold/rented.