There is a film about two women who meet seemingly by chance. One is an entertainer, but they both appear to switch their identities, and both are involved in trying to solve a mystery that entails a body in a bed in a mystery house that seems to defy the normal logic of time. Fans of David Lynch may immediately cry Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001), and they would be right. But there is another film, with a similar narrative description, but with quite a different approach, separated by an ocean and 26 years, and it is called Celine and Julie Go Boating (Jacques Rivette, 1975).

When two works of art have such notable similarities, one tends to wonder if the latter is influenced by, or a comment in some way on, the former. Or perhaps they both have something to say about a particular subject. In this essay, I intend to look at both films and see what connects the two, and what possible statements they may have been making.

Rivette and Lynch came from quite different routes to their film making life. Rivette was one of the film fanatics who gathered at the Cinematheque Francais in Paris, run by the irascible Henri Langlois. Langlois was a notorious archivist and collector, and he would show films, usually without license, to packed rooms, in corridors, in basements, to voraciously hungry young French cinema fans. These cinephiles would then debate the merits and failings of the films all night, and several went on to write for the prominent Cahiers du Cinema journal in the 1950s. Cahiers was founded by Andre Bazin, a film theorist who formulated Auteur Theory, which stated that the film was an art form on a par with the novel or painting and as such had the imprint and direction of one artist in it, that artist being the director. It is impossible to underestimate the influence of Bazin and his theory to these young writers, weaned as they were in Langlois’s temple of cinema on the likes of Alfred Hitchcock, Nicholas Ray, Orson Welles and Robert Bresson. Several of this pack went on to direct their own films, namely Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, Francois Truffaut, Agnes Varda and Jean-Luc Godard. They rebelled at what they called “cinema du papa”—“a certain tendency of the French cinema” as Truffaut called it; the old, established, studio style. This movement became the French New Wave and it changed cinema forever, and not just in France.

David Lynch was and remains an artist. He was a painter, and carpenter, and it was only when the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts offered him funding to make an experimental short in 1967 that Lynch took to film making. Lynch wanted his paintings to live, to move, and so his early short films (Six Figures Get Sick, The Alphabet,, The Grandmother) all heavily feature animated sequences and stop-motion. Unlike Rivette, Lynch has never considered himself a cinephile, nor has he written film criticism. One connection there is, though, is through Andre Bazin and Auteur theory: David Lynch is widely acknowledged as American cinema’s foremost and most distinctive auteur.

Looking at Celine and Julie Go Boating and Mulholland Drive one could immediately point out the substantial differences between the two. One is a “poisonous valentine to Hollywood”, the other a magical mystery trip into an apparently haunted house. One is a dark work of lust and lost dreams, the other a sunny breeze through a haphazard misadventure. And yet there are substantial similarities. They both follow two women who seem able to exchange personalities as the narrative progresses. They both accept magic realism into their mundane worlds, where the surreal and supernatural exist in the cafe and the diner of normalcy.

Both involve a mystery and a body in a bed, and both concern the nature of performance and fiction.

To further understand these similarities and differences, and how they can give a deeper understanding of both films, I shall now look into each one in more depth.

Celine and Julie Go Boating

Rivette’s first two features (Paris Belongs to Us and The Nun) were well received, though the director since expressed dissatisfaction with some of his decisions in the creative process. The tumult around the events of May 68, and a growing interest in improvisational theatre, led him to re-assess his artistic direction.

“… after the experience of my first two films, I realised I had taken the wrong direction as regards methods of shooting. The cinema of mise en scène, where everything is carefully preplanned and where you try to ensure that what is seen on the screen corresponds as closely as possible to your original plan, was not a method in which I felt at ease or worked well.”

(from an interview with Rivette by

He gathered a large group of actors who could go with his new, improvisational, direction and this freewheeling approach first produced Mad Love (1969). Though well received, Mad Love was just a precursor to the monumental Out 1, a thirteen hour opus of multiple narrative strands and characters in numerous episodes that unfold and reveal more at a very leisurely pace. As well as improvisation and allowing the camera to keep rolling, even capturing things that would normally be cut or considered mistakes or “behind the scenes”, Rivette believed that the film truly came to be in the editing, or montage, in the original sense as laid out by Soviet theorists like Dziga Vertov.

This extended, free form, style continued with Celine and Julie Go Boating, though this time the running length of three and a half hours, while still long, is a serious step down from Out 1. Although both were long films, Rivette was able to shoot on a tight schedule (under six weeks for each), mostly due to him using very long takes, allowing improvisation and “mistakes” to be included.

Celine and Julie Go Boating is almost two films, connected by the two characters. The first one concerns the two eponymous characters meeting, getting to know one another, and their lives together. The second part concerns what could best be described as a haunted house, where staid and maudlin characters repeat a melodrama that the heroines intrude on and involve themselves in. Our first view of either character is Julie, in a sunny Paris park, reading a red book entitled Magic. She has large glasses and, as we see later, she is a librarian. Julie is the more conservative, conventional, of the two, unlike Celine, who breezes into her life with more exotic clothes, her life possessions in a tote bag, in a tearing hurry, dropping things in a breadcrumb trail that Julie collects as she gives chase.

Straight away, the film telegraphs numerous tales that are relevant: the Hansel and Gretel tale, of the house in the woods; Alice in Wonderland, where we, and Julie, follow the white rabbit down the hole into another world of magic and myth. And the book she is reading, entitled Magic, as she casually draws a triangle into the sand with her feet. Could Celine be a magical creation, to enlighten her otherwise mundane existence?

After pursuing her through Montmartre and up Sacre Cour, during which Celine could have caught up with Julie several times but instead they acted like they were children playing games, Julie catches up with her at a small hotel, where they share a joke and a drink.

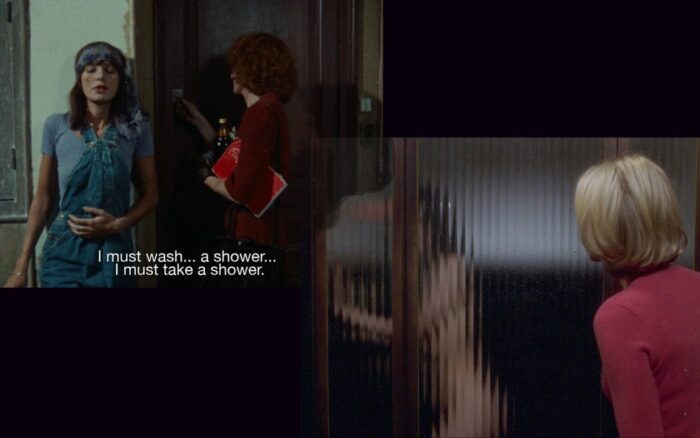

The next day, we see Celine at her day job, in a library. Behind her we—and eventually she—see Julie, flipping idly through books. Here we see an early example of the two characters mimicking, or echoing, each other. Celine is bored and coating her fingers with red ink and printing hand shapes in the library books. Meanwhile Julie is drawing round her hand with a red marker pen in the library books she is similarly disinterested in. When Julie leaves, Celine again follows, but this time loses her. However when she returns home she finds Celine waiting outside her apartment. As if she already knew her, Julie invites Celine in, where she has a shower, recounting her various and clearly fantastical adventures in Africa and the Far East, that Celine listens to and comically accepts without question. From then on they live together in the apartment, their relationship as undefined as much of the rest of the narrative details.

So far, so Mulholland Drive, with a mystery woman entering another woman’s life and moving in with her after a shower. In Lynch’s world, however, the lesbian affair is front and centre, the despair of frustrated love, and lust, leads to the murderous tragedy at the end of the film, as opposed to Rivette’s heroines, whose relationship is never clarified or questioned, and is not the emotional thrust of the narrative.

Mulholland Drive

Mulholland Drive begins with a road accident on the eponymous route. An unnamed, glamorous, woman (Laura Harring) survives the car crash and stumbles, dazed, down the hillside and takes shelter at a Beverley Hills apartment. At this apartment is young Betty Elms (Naomi Watts), a bright eyed young aspiring actress here in Hollywood to fulfil her dreams. She finds the woman, who calls herself Rita (after seeing a Rita Hayworth poster on the wall), in the shower, and when they meet, learns she is suffering amnesia after her accident. Once together, the spritely Betty decides they can find out who Rita really is by engaging in a Nancy Drew style investigation. Their trail, after being reminded of a name (Diane Selwyn) at a diner, takes them to a seemingly empty house that they break into, where they find a body in a bed. They flee, deeply disturbed. Back home they don blonde wigs, to apparently disguise themselves from whoever had killed the mystery woman. That night they consummate their relationship. Then Rita awakes at 2am, insisting they go to a theatre called Club Silenco, where they see a bizarre performance that defies audience expectations of sound and performance, where a singer collapses during an emotional performance of Roy Orbison’s “Crying”, but the sound and singing continues as she is carried away, unconscious. Betty finds a blue box in her purse that matches the blue key Rita had earlier found in her purse. Back at the apartment, Betty disappears while Rita is in the bathroom. She sees the blue box on the floor, opens it with the key, and the camera and, we assume Rita, enters it.

The rest of the film follows hard on her luck and washed up actress Diane Selwyn, played by Naomi Watts, living in the apartment Betty and Rita investigated. She is invited to a party by her former lover Camilla Rhodes, played by Laura Harring, where Camilla announces her engagement to a director Betty saw and recognised at a rehearsal. Later, at the diner where Betty and Rita went, Diane arranges for a hitman to kill Camilla. Back at her apartment, a depressed Diane is tortured by memories and hallucinations of her past, before she runs into the bedroom, dives into the bed and shoots herself.

Mulholland Drive sees two women who meet by chance engage in an investigation into a mystery house, where they have seen a body in a bed. It is split into two parts, where the identities of the women change and are changed. They enter this house, and the “other reality”, via the talisman of the blue box and the key, a transition which is achieved by Celine and Julie by the talisman of the boiled sweets they find in their mouths.

Celine and Julie Go Boating Down Mulholland Drive

The key to both films rests in two related matters: the nature of fiction and agency in the creative act, and the nature of identity. In Mulholland Drive, Betty (Naomi Watts) is an actress, all wide eyed and innocent, come to Hollywood to make it big and fulfil her lifelong dream. In Celine and Julie Go Boating, Celine (Juliet Berto) is a stage performer and magician, who performs cabaret acts to mildly interested audiences. At one point, a heckler calls out that it is all fake, as if magic was a real thing. Perhaps he is to be forgiven, given the magic that actually happens in the rest of the film. Celine’s manager and agent tells her he has arranged an international tour, and brings three suits in dark glasses, ostensibly big talent scouts, to watch her perform. Thus another parallel between the two films, where Betty (Mulholland Drive) and Celine (Celine and Julie Go Boating) have an audition.

Betty and Celine fair quite differently in their auditions, however. While Betty seems to cross into the scene she is playing completely, with tears and passionate kisses included, Celine does not even attend her audition: she is otherwise unavailable and Julie (Dominque Labourier) dons the costume and makeup and takes to the stage as Celine. Julie breaks through the fiction of the performance in an entirely opposite way, when she starts berating the men as voyeurs, perverts and masturbators, running from the stage and out down the steps that she ran up in pursuit of Celine at the start of the film.

Celine and Julie’s exchanging identities brings to mind the nature of the performer, that we are an audience watching a fiction. Rivette’s improvised style, with long takes and inclusions of what would normally be considered mistakes, only adds to this. We could be that heckler who shouts that it is all fake, but there is scant attempt to make it seem real. In Rivette’s world, we are aware that we are watching actors in a performance.

This is one of the fundamental differences between this and Lynch’s film. There is no breaking of the fourth wall in Mulholland Drive. While the nature of performance and the transitory nature of identity may recall the state of acting and performance, Mulholland Drive is entirely self contained as a film. In some instances, the styles of Celine and Julie Go Boating more recall Lynch’s next film, Inland Empire. Inland Empire concerns a film being made, the actors and director involved, a mystery house that appears to take Nikki Grace (Laura Dern) into the fiction she was playing as a reality. I would further point to Lynch’s self-shot, semi-amateur video style as being more akin to Rivette’s simple set ups and long takes than the luxuriant cinematography of Mulholland Drive.

What is common to Celine and Julie Go Boating and Mulholland Drive (and Inland Empire) is the device of what I will call the magical space. In Celine and Julie Go Boating, this is the haunted house where a drama is being replayed by automaton actors oblivious to the two heroine interlopers. In Mulholland Drive, it is the blue box that we go into, that the darker, second half, of the tale transpires within. Inland Empire, too, has such a space, the house that is on the set of the film they are making.

In all cases, it is in this space that the normal rules of time, space, identity and personality are suspended. Events can be repeated ad infinitum, without those involved being any the wiser. Indeed, repetition is an identifying marker of these spaces, signifying that plays, movies, TV series and auditions can be repeated again and again, and yet we invest in and believe in the drama each time. As such, the emotions are real, even if they are faked. We feel the same response to them when we watch them again.

That is the response as a viewer. As a performer, be it the actors or the director, that magic space is the world within the cinematic frame that they must create ,where their actors can produce this believable fiction for us to view. There are different devices and approaches to this notion of realism. Rivette chose a more Brechtian approach that would break the fourth wall by including mistakes, having simplistic lighting and set ups, long takes, over the top makeup etc. Lynch is entirely within the world he has created. His film is set in Hollywood, it is to a great extent about Hollywood, a system that is called the dream factory, but often uses people up and discards them, turning the dream into a nightmare. He employs many devices of Hollywood films (thrillers, melodramas, love stories, musicals, noirs) to comfort-trick us into accepting the subversive devices he smuggles in. Lynch has used such devices before, using his mise en scene and narrative to make us, the viewer, question our role and what we are viewing. Remember the scene in Blue Velvet (1986), in Dorthy Vallens’s apartment, where Jeffrey Beaumont is watching through the closet slats, where we are as much the voyeur as he is, the question of who is the voyeur directed not only at the character Jeffrey, but at us, the viewer.

That both Celine and Julie Go Boating and Mulholland Drive have prominent scenes set in theatres, where the performers break the fourth wall in different ways, does not detract from the different approaches to fiction and realism that the two directors took. Both scenes in each film say “yes, this is fake. And you in the audience know it is fake, just as we know our performance is fake when we are your audience. But you feel the emotions just the same.”

The fake feels real.

In both films, the heroines are embarked on a mystery quest, involving identity and a fictional girl. In Rivette’s film, the girl is called Madlyn (perhaps a reference to Proust’s memory-inducing madeleine cakes?), she is a child and is one of the characters in the melodrama in the haunted house. Celine and Julie, using their talismans of the boiled sweet to enter this world, break all manner of fourth walls within it (changing wigs and costumes, fluffing their lines, even changing the record in the diegetic soundtrack of the scene), and somehow are able to rescue the girl that they know is to be murdered by story’s end. They escape the house, with the girl’s help, and flee with her to their own world, where she is found, like Lynch’s Rita, in the bathroom. Betty and Rita, on the other hand, are trying to find out who Rita is after a road accident on Mulholland Drive plunges her into amnesia, and she stumbles into Betty’s aunt’s apartment, where Betty is staying. Their search brings them to a house that has a corpse in the bed, that triggers a psychological breakdown in both characters. After they view the wall-breaking performances at the Club Silencio, Rita finds the blue box opened and she, and the camera, plunge into it.

Here again is a substantial difference between Rivette’s film and Lynch’s. In Celine and Julie Go Boating, the young Madlyn is rescued and then the heroines appear to re-start their adventure, with the roles reversed (Celine sits reading the magic book while Julie rushes past dropping things). In Mulholland Drive, the body is both the alternate/real Rita (Camilla Rhodes) that Betty (Dianne Selwyn) had killed, and it is Dianne’s body (Betty) who kills herself at the guilt and depression over her failed love and dreams. (As an aside, the narrative ends where it began in the two Lynch films that straddle Mulholland Drive—Lost Highway and Inland Empire.) In Lynch’s world, the fourth wall is not broken and the characters cannot escape their tragic fates. In Rivette’s world, the girl is rescued, but her fate and the fate of her rescuers, is perhaps to repeat themselves again and again.

At the end of Celine and Julie Go Boating, the three girls (Celine, Julie and Madlyn) are seen idly enjoying a boating trip on a lake in a Parisian park. (As an aside, the French term “aller en bateau”, to go boating or on a boat ride, also carries the colloquial meaning of “to get caught up in a tall tale told by someone else”). They see the characters from the haunted house, still made up, frozen in their poses, on another boat that passes them in the opposite direction. This made me think of a song that tells one to “row row row your boat”, just as Celine, Julie and Madlyn are doing. The song is a round, with multiple voices singing in repeat one after another in a chorus. This could be an apt metaphor for Rivette’s film, and for Lynch’s, especially the end couplet:

“Life is but a dream.”

Terrific, well-informed, and insightful piece.