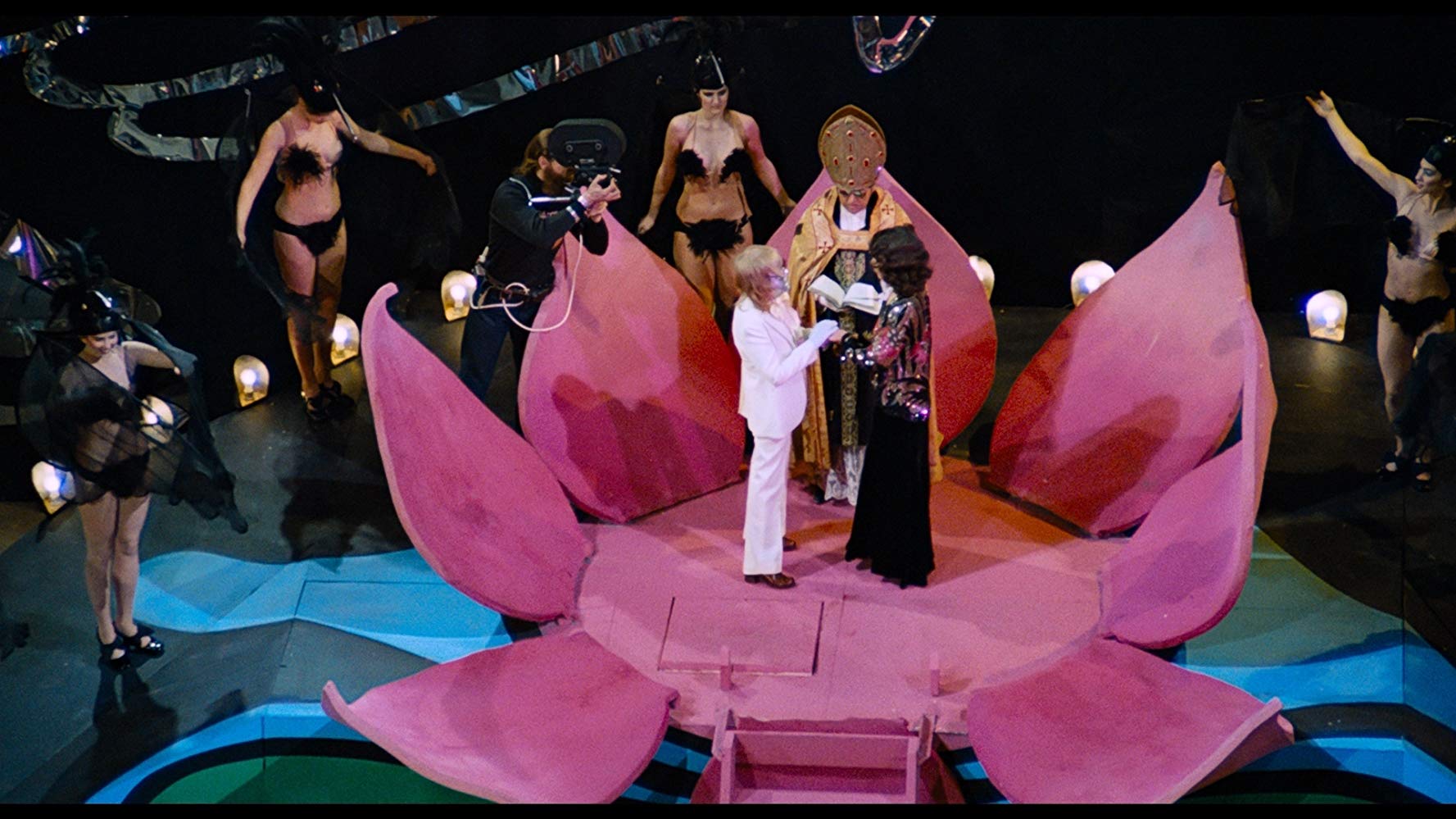

Brian De Palma is the Ohio weatherman of cinematic ambition. There are times in the week where his grasp of the elements and intuition guide him towards the right answers and times when his hubristic call for a sunny day means an audience that wishes they brought umbrellas. This is to say that De Palma is an artist at his best when he aims for the impossible. By that metric, the quintessential film might be Brian De Palma’s mad musical dream, The Phantom of the Paradise. Equal parts baroque, funny, violent, and frantic, the horror-satire-rock-n’-roll-musical-comedy is the director’s masterpiece.

The 1974 film starring William Finley, Paul Williams, and Jessica Harper struts and wails with all the unique strangeness of De Palma all while obeying the rules of convention for the melodramatic musical. One can almost picture the imaginary source material: a flattened, sweaty off-Broadway that birthed De Palma’s madcap adaptation.

A villainous music producer, Swan (played by actual music genius Paul Williams who wrote the film’s music), steals the music of tortured artist Winslow (played by William Finley) then frames him for drug possession. When the desperate Winslow escapes the prison and seeks justice, he’s injured and becomes the scarred and brooding Phantom, determined to destroy Swan and his club, the titular Paradise. Caught between the two is the hypnotic ingenue and talented singer, Phoenix (played by Jessica Harper).

Story elements from Marlowe’s Faust, Hugo’s Phantom of the Opera, and Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray commingle to create a tale that feels classic, like a work of antiquity set in modern times. In this case, it’s set against the sweat-soaked, cocaine-encrusted frenzy of 1970s rock n’ roll. More than anything, Phantom brilliantly functions in two ways: as an exploration of the form (in this case, the form of the musical) and a satire of the setting.

Exploration of Form

Everything from the film’s opening number, a story-song in the vein of Don Henley’s ‘American Pie’ by the fictitious Beach Boys pastiche The Juicy Fruits, to its final moments places us firmly in the camp of, well, camp. De Palma knows musical theatre and understands the internal logic (or lack thereof) in its narrative mechanisms. The film’s obsession with songs-as-expression and reductive treatment of certain plot points highlight this knowledge.

For example, when Jessica Harper’s character faces the notorious casting couch, De Palma turns this into a choreographed dance in the background. Starlet after starlet jumps on the couch, gets ravished by a jean-jacketed oaf, then rolls away for replacement. Like a stage musical, Phantom of the Paradise gives its audience all it needs to know in a few key visuals, more interested in symbolism than outright depiction. A similar treatment exists in Winslow’s persecution, harassment by police and escape from prison. These are necessary to the plot but irrelevant to De Palma’s emotional arc. Thus, he cooks them down into opulent signifiers.

When it’s time for music, however, De Palma grants loving attention to each note and gesture. He uses the music of the film to give insight into the inner monologue of the characters. De Palma’s musical numbers become exposition, not of the plot, but of feeling. He obliterates the subtleties of the human heart amidst blasts of synth and guitar.

When the wounded Winslow returns to The Paradise to confront Swan, he simply finds the mask and becomes the phantom. However, it doesn’t turn into a generic Vincent Price-esque slasher revenge film. Swan traps the scarred and vulnerable Winslow into another devil’s bargain for musical perfection, fame, and the chance to turn his beloved Phoenix into a star. De Palma is not content with a horror film, a musical, a comedy, or a biting satire. He wants all of it on stage, parroting the excesses of the story’s setting.

Satire of Setting

Above any genre convention or label, Phantom of the Paradise exists as a testament to its time. Paul Williams not only stars but also contributes his musical talent and “been-there” candor to the proceedings. This blesses the film’s portrayal of music with the kiss of one of its Popes. Every character glistens, baptized in the sleaze of an early, ballsy De Palma.

Like Paul Thomas Anderson’s love letter to the seedy porn of Los Angeles’ Golden Age in Boogie Nights (1997), Phantom is interested in the people, places, and things that made up a world De Palma longed for. Swan’s crisp suits, greased smile, and mirrored full of writhing women act as garish dreams of an outsider looking in. This is De Palma fogging the window to rock n’ roll’s hedonistic delights.

There’s also a dark side, as De Palma exposes the sadism of the business behind the music. Jessica Harper’s Phoenix is cruelly buffeted from humiliation to humiliation before her big break, her wide-eyed wonder at every abuse and opportunity acting as a first verse to the song she would later dance to in Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1978). Swan’s appetites don’t just limit themselves to sex, money, and fame. He craves eternal youth and the domination of others, the way artists can become predators when corrupted by the business.

Fade Out

Brian De Palma lends his usual idiosyncratic style to Phantom of the Paradise while also bowing to both the musical and the rock music scene as style elders. It’s a dark, violent mood symphony as funny as it is emotionally harrowing. We decide an auteur’s success by his riskiest endeavors and this is Brian De Palma’s masterpiece.

Perfect Double Feature: Nothing skewers showbiz Peter Jackson’s pre-Lord of the Rings sex, drugs, and puppets trash anthem. The only double-feature candidate is Meet the Feebles (1989).

And the Juicy Fruits were a send up of a 50’s band singing “Goodbye, Eddie, Goodbye.” The Beach Bums sang “Upholstery” in the style of the Beach Boys. Same guys, different genres.

Don Henley’s ‘American Pie’ should be Don McLean’s ‘American Pie’.