Desperate Souls, Dark City and the Legend of Midnight Cowboy (2022, dir. Nancy Buirski) is far from being another “making of” documentary. With its commentary of staccato supercuts covering both the film and culture surrounding it, it exists as both a recounting of the film’s legacy and a reminder of the time in which it was created.

Interviews take on an almost monolithic quality in Desperate Souls. Being shot in both extreme close-up and shaky-cam, the result is as intimate as it is alienating. The very same shots which make every interview seem like a close conversation also keep it feeling as if looking up at goliaths, taking up the whole screen with their visage.

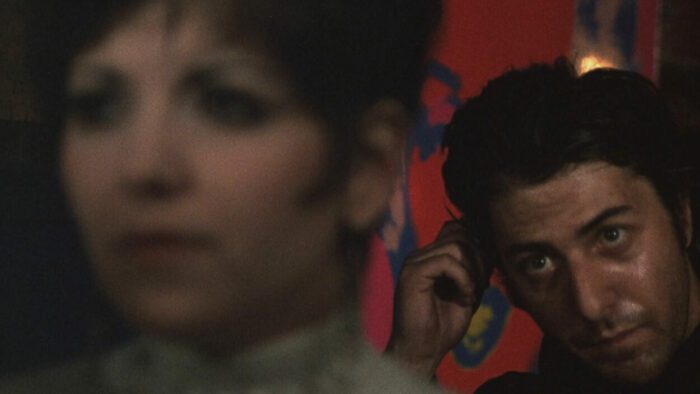

Assembled as nearly a series of vignettes on topics, actors, authors, and critics recount the making of and legacy of the film. Accompanied by a montage of scenes and beats of Midnight Cowboy (1969, dir. John Schlesinger), the news, and other films mentioned in interviews, Desperate Souls comes across as the film buff’s version of Framing Agnes (2022, dir. Chase Joynt).

If there’s one thing Desperate Souls refuses to shy away from, it’s discussions of Midnight Cowboy and queerness. John Schlesinger, as noted multiple times throughout the film, seemed intent on portraying a type of male intimacy that hadn’t been widely seen. While Joe and Ratso don’t share sexual intimacy, they do care for each other and share an emotional one.

There’s a discussion of history in the film which comes across as important as anything to do with it directly. The political climate in the 1960s could perfectly lead up to the creation and release of Midnight Cowboy, and it almost felt perfect for the era. At a time when frank discussions of war left Americans clamoring for something more real and gritty, Schlesinger was there delivering just that.

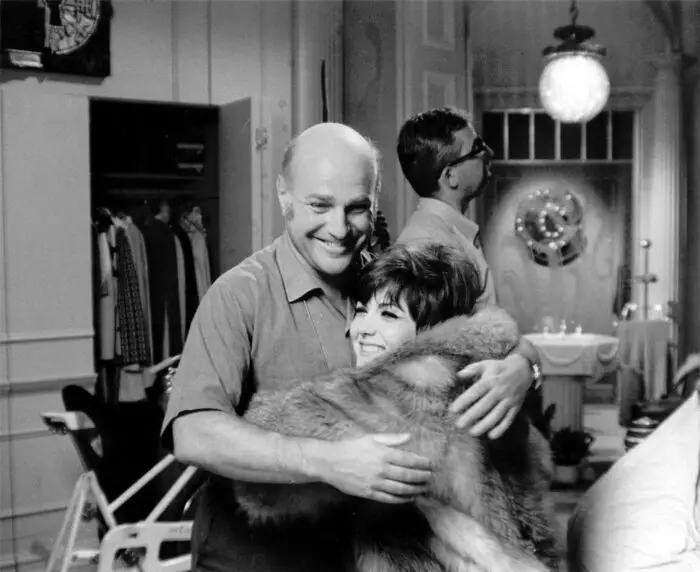

In many ways, Desperate Souls is as much about Schlesinger himself as it is about Midnight Cowboy. There are instances in which art cannot be separated from the artist, and it seems clear that director Nancy Buirski believes that to be the case here. The central conceit of the film is not that it was something the cast knew would be great (just the opposite, in fact) but that it was filled with Schlesinger’s voice in a way that made it great.

Perhaps the strongest note in the film is its blunt discussion of Schlesinger’s homosexuality. In a time where there seems to be a new gay panic and attacks on the entire LGBTQ+ community, it all seems especially poignant. This a film made by a gay director, where he did more than explore depictions of “limp-wristed” gay men. Even if scenes of intimacy would be cut for television, they exist in the film proper and make it stronger.

It’s no secret that many queer people turn to sex work when faced with employment discrimination. By adapting a story largely about sex work, Schlesinger was able to bring his own expressions of queer intimacy into the film, allowing resonance with audiences across the decades.

As Desperate Souls notes, even the original cowboys themselves were largely queer. The history of the cowboy is plagued with revisionist history, much of which has seen a reconciliation through the revisionist Western. For the explorations of sexuality in Cowboy, there couldn’t have been a more perfect script.

Maybe it was that aforementioned queerness that gave Midnight Cowboy its original X rating. As Desperate Souls notes, however, it changed nothing to later be given an R. As the first and only X-rated film to win the Oscar for best picture, Midnight Cowboy created for itself a niche in cinema history. Happy to explore this, the film focuses on the parts which would later become more acceptable, including the films which largely exist due to this broken ground.

It’s difficult to believe that any X-rated film could win an Academy Award today, regardless of the subject matter. Maybe that speaks more to the time than to Midnight Cowboy itself, but the film’s focus on this cannot be overstated. As one of the latter points the film makes, it stands out as nearly being a call to action, something that begs audiences to take every film more seriously, regardless of rating or subject matter.

Far from being only socio-political commentary, plenty of time is spent making Desperate Souls worth the watch for those who just want to hear about Midnight Cowboy. Jon Voight even shares a story of when he lied to Schlesinger after the last shot of the film.

“I grabbed him by the shoulders and I said ‘Jon, we will live the rest of our artistic lives in the shadow of this great masterpiece,’” Voight recounts, laughing. “I said the most ridiculous thing I could think of.”

Fortunately for us all, Voight was accidentally correct all those years ago.

With a fascinating collection of stories and perspectives, Desperate Souls, Dark City and the Legend of Midnight Cowboy is a documentary that neither overstays its welcome nor needs to try too hard to be interesting. The film feels more like a group of friends sharing stories than a series of interviews on a subject and uses the charisma of all of its interviewees to create a film that stands on its own. Perhaps without ever consciously trying, Buirski’s film shines a spotlight on Midnight Cowboy without ever getting stuck in its shadow.