Pictures of Ghosts (Retratos Fantasmas), from the acclaimed Brazilian director Kleber Mendonça Filho (of Bacarau, Aquarius, and Neighboring Sounds), confidently transgresses traditional genre boundaries to meditate on filmmaking itself. By turns smart and sly, rueful and optimistic, pedestrian and poetic, Pictures of Ghosts brings viewers on a journey through Mendonça Filho’s cinematic past, the filmmaker himself narrating as scenes unfold from his childhood, his filmmaking, and his uncertain present. Brazil’s official entry for Best International Film (and for Best Documentary Feature) at the Academy Awards, Pictures of Ghosts is by no means conventional—in many ways, it’s intensely idiosyncratic—but it’s nothing less than a treatise on cinema itself.

The film is woven together through an unlikely web of source material. There are historical documents and maps, architectural designs, aerial photos, family snapshots, and home footage from Mendonça Filho’s life in Recife, the Brazilian coastal capital of Pernambuco where he lived as a child, presented at first in such an objective, detached tone it’s hard to discern just what point is being made or what direction the film will take. There is, even, a picture of a ghost, one lending the film a literal (if not sufficient) interpretation of its title. And there is a focus on the apartment the filmmaker and his family once inhabited.

The story told there, in the film’s first act of its triptych, is one of that apartment and its surrounding neighborhood. There, when he was a young boy, Mendonça Filho watched his mother conduct research and interviews for her oral history projects, and he began his own journey into filmmaking, shorts he wrote and directed and cast with his friends and neighbors. As Mendonça Filho narrates, clips from those first efforts are interspersed with home-movie footage of the same friends and family who act in them, discreetly blurring the lines between fact and fiction. At one point, Mendonça Filho recalls hearing his family dog, who had died years ago: it was a broadcast of one of his films on public television, its soundtrack filtering through the open windows of the neighborhood. It seems a lifetime ago that an entire community might be watching the content on the same channel at the same time.

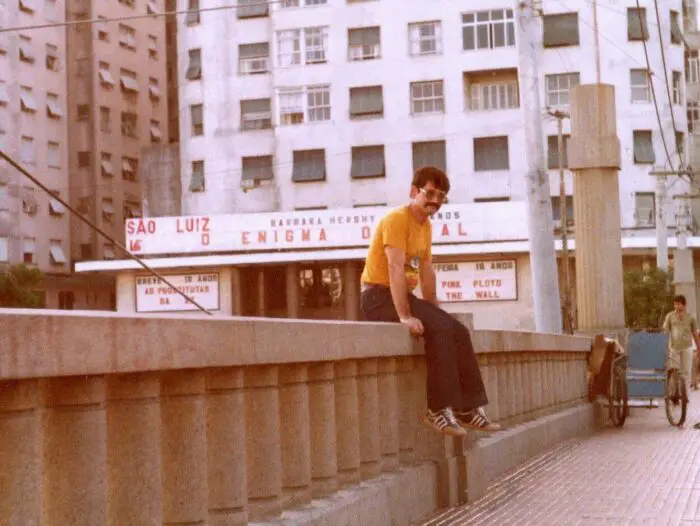

The film’s second act focuses less on the filmmaker’s family home than on his second home, so to speak: the once-grand movie palaces of central Recife, most of them today long gone, where he continued his cinematic education and which formed a rich part of the city’s thriving identity. The were, for Mendonça Filho, a place to see the magic of both Brazilian cinema (Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands, Bye Bye Brasil, Era Uma Vez Brasília) and Hollywood exports (Rocky, The Witches of Eastwick, A Clockwork Orange, The Fly, Die Hard, They Live) and dozens of others making for a curious cobble of a syllabus in filmmaking, which formed not only, he contends, a rich part of his own experience but also of the collective memory of the city. Today, with so many big-box multiplexes offering little but generic anonymity, the moviegoing experience has lost its je ne sais quoi. Today in Recife, of these only the São Luiz cinema still stands. The others: pictures of ghosts.

In the film’s third act, Mendonça Filho, riding in a cab, converses with his driver about his work in the industry, as what begins as a casual conversation turns into an occasion for deeper reflection. What is it, exactly, a filmmaker does, really? It’s an innocent question with existentialist implications. And it gives the filmmaker pause. As the cab continues its journey, we see the filmmaker ponder his city, his past, his life, his work. It’s an elegant scene and one that draws the film to its close. And then you realize it must be a fiction, or at least an intentionally staged sequence, filmed with multiple cameras and a willing participant ready to ask his lines that could not have not been composed. Pictures of Ghosts may be, technically, a documentary, but it is a documentary where the filmmaker is, as a filmmaker will, artfully pulling each puppeteer’s string to make a work of art from his material.

Whatever it is, exactly, and the term documentary surely fails to describe it in full, Pictures of Ghosts is mesmerizing, a wholly personal and often poetic reflection on a life lived in cinema and a city once immersed in its art. There may be, literally, a picture of a ghost from the filmmaker’s childhood apartment, but more figuratively, the picture of ghosts in a nonfiction film about the past are many: the great movie palaces, once thriving hosts of community and conviviality, are today mere haunts, nearly forgotten sites of hopes, dreams, and progress, gone now, except in the memories of those who frequented them, and in Pictures of Ghosts.