For a brief time in 2022, the Chinese love story Return to Dust was a massive success, both abroad, nominated for a Golden Bear at the 2022 Berninale, and in director Li Ruijun’s home country. Made for just $275,000, the low-budget arthouse drama leapt unexpectedly to the top of China’s box office with nearly a $15 million take in its first two weeks. A simple love story of the arranged marriage between a humble farmer and his chronically ill wife, Return to Dust won over audiences with its authentic performances, understated narrative, and impeccable cinematography.

And then it disappeared.

Without warning or announcement, on September 26, 2022, the film simply ceased to exist in China. Despite audiences’ rapturous reception and its heady box-office performance, Return to Dust no longer screened at any Chinese cinema, nor was it available to stream on any service. Mentions of the film were scrubbed from social media. There was no announcement regarding its censorship from the Chinese government—only its foreboding, complete absence.

On the surface, the story told in Return to Dust seems hardly the kind that warrants censorship of any sort. It is as sweet and compelling a love story as one can imagine, set outside any obvious political or ideological struggle. Reviewers rightly praised the film as one of China’s finest in recent memory, and at first glance its primary virtue seems its directness and simplicity.

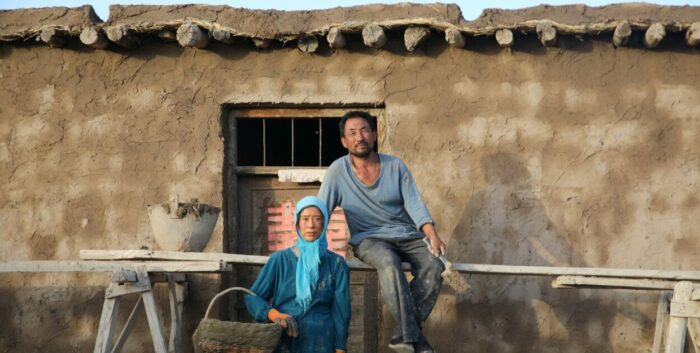

Taking place in 2010, Return to Dust begins with the arranged marriage of two lonely, middle-aged villagers whose families are eager to cast them off. Cao (Hai Qing) is shy and timid, a woman suffering from suffering from chronic illness and an unnamed disability, almost incapable of human connection. Ma (Wu Renlin) is an unassuming farmhand with little to his name and no prospects. Together, the two outcasts set about fixing up a small patch of land in the small, rural village of Gaotai, where despite her weakness Cao offers the hardworking Ma what physical help she can.

Though the two barely speak, they find a connection in their shared purpose of building a home. The work is hard: Ma molds individual bricks from mud, the two weave together straw floors and thatch for a roof, and the earth is tilled by hand. In the few moments when the couple are not hard at work, a bond between them grows. Ma is not only hardworking, a talented farmer and builder, but good-natured with a dry sense of humor. Cao slowly sheds some of her inhibition to treat her new husband with warmth. It’s not a passionate affair—their tender moments are marked by nothing more than a slight embrace or gentle touch—but it’s a meaningful and convincing one nonetheless.

Over time, the skillful Ma, with Cao’s assistance, has built from nothing a serviceable, sustainable small farm and home. Chickens provide eggs, corn his crop. Their mudbrick edifice becomes a true home. Cinematographer Wang Weihua’s compositions are impeccably lit and carefully choreographed with all the impact of a Rembrandt or Vermeer, though they never feel artificial or staged. The film’s visual design is nothing short of a minor miracle, making cinematic art from simple images of the farm couple at work and at rest. Pausing the film at nearly any moment in its 133-minute runtime will yield an image worthy of an elaborate frame.

Those images are not only aesthetically beautiful but also, from a narrative perspective, intentional. A brief shot of a bird feeding the young hatchlings in her nest suggests Ma is considering the possibility of raising a family with Cao, though her disability makes childbirth seem unlikely and no dialog (or sex) between the two of them raises the prospect. Rather, the two tend to their chickens and their crops as they would dote over a child. Lead actors Wu Renlin and Hai Qing deliver understated, economical, and completely convincing performances as a couple who learn, over time, to find love with one another even in the harshest of circumstance.

One might reasonably wonder what could possibly be so controversial in such a tender love story to warrant censorship. Outside in the dying rural communities of the Gansu province surrounding the couple, the government is incentivizing local farmers to demolish their homes and move to the city in the relentless march towards urbanization. All around Cao and Ma, farm livelihoods are disappearing, just as they work to establish their own. Online, some complained that the film’s focus on the simplicity of farm life is at odds with the image of itself the Chinese wish to convey on an international stage. And clearly, the film does not endorse the government’s subsidizing razing small farms to make room for urban development, and its sympathies lie with the hardworking laborer rather than the developers who exploit them. Yet, even then, such readings seem secondary to the profound love story at the film’s narrative center.

Regardless of the reasons for Return to Dust’s disappearance from Chinese theaters and streaming services—it remains impossible to see even today, nearly a year after its release, anywhere in Li’s home country—this remarkable film deserves to be seen by as many viewers in as many countries as is possible. Ruijun’s sixth feature, a true triumph of independent cinema, pits his two very human protagonists against the rapid urbanization of his native region, and now, in the wake of the film’s censorship, the individual auteur against an oppressive government.

Return to Dust, directed and written by Li Ruijun and starring Wu Renlin and Hai Qing, opens Friday, July 21, 2023 in Brooklyn, with additional markets to follow. In Mandarin with English subtitles, 133 minutes.