Having read 1984 isn’t necessarily prerequisite to viewing the new documentary Total Trust, but Jialing Zhang’s daring film so soberingly charts China’s contemporary surveillance state that it practically brings George Orwell’s omnipotent, omniscient (but once-fictional) super-state to life. With the patient deliberation of a methodical prosecuting attorney and the keen empathy of an astute therapist, Zhang focuses—rather miraculously, in ways I’ll try to chart—on those whose lives have been disrupted by their country’s Orwellian surveillance tactics and social-credit schemes. That this documentary could be made at all is in itself surprising; that it could be made with such clarity and economy is remarkable.

Jialing, an Emmy-Award nominated independent filmmaker, is Chinese born but based in the U.S. It’s not likely she will ever return to her homeland, given her prior work In the Same Breath (2021) and the Sundance Grand Jury Prize winner One Child Nation (2019). Her Total Trust, though it is shot entirely on location in China, is directed “from” abroad here in the States and focuses predominantly on three women, two of whom are fighting for the release of their husbands: Wenzu Li, whose husband Quanzhang Wang, was one of more than 300 lawyers and activists arrested in 2015; and Zijuan Chen, whose husband Weiping Chang, also a civil-rights lawyer, was arrested in 2020. The third woman, Sophia Xueqin Huang, is a journalist who befriends and supports Chen in her quest.

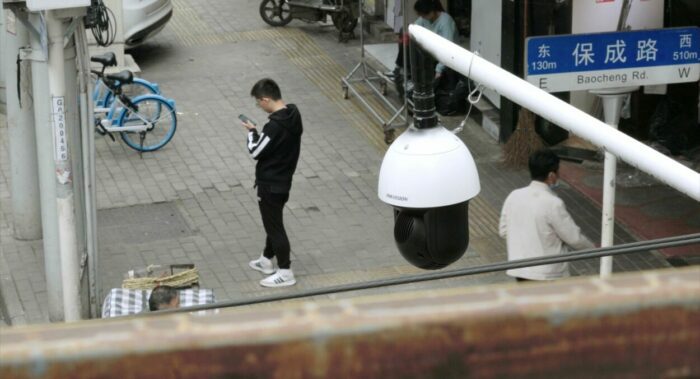

What these women face is appalling. In China, it’s estimated that half a billion cameras are pointed at its citizens. Watch programs reward neighbors for spying on and reporting each other. Workplaces monitor employees’ biomimetics for stress levels. An intricate network of databases charts each person’s perceived threat or allegiance to the Communist Party. Facial recognition software is just one of the means by which citizens are tracked; voice recognition, for example, helps identify individuals even when masked. And a point system of social credits, while it benignly rewards good citizenship—a long volunteer shift might earn one enough credit to buy, say, a new pair of chopsticks—its penalties, especially for civil protest, are debilitating. Activists and journalists are jailed, even tortured, dare they protest the Party line.

Jialing’s method in Total Trust is to present these widespread, practically ubiquitous surveillance measures through the eyes of her three protagonists. There are, as their might be in a more traditionally expository documentary charting the phenomenon, no “talking head” experts interviewed on the matter, no lower-third chyrons, no voice-over narration explaining the images, and no charts or data; instead, Total Trust is the intimate story of the three women whose lives are dramatically impacted by the government’s surveillance methods. There is no room in modern China for dissent.

Somehow—we are not to know how—Jialing has had her cinematographers, if that’s the right word, embedded up close and personal with each woman and her family. Chen has not seen her husband since his 2020 arrest on the vague charge of “subversion of state power.” She and their son protest, if futilely, his imprisonment, unable to see visit him but hearing chilling reports of his torture, while surveillance cameras chart their every movement. Journalist Huang is covering his case, but her doing so raises the suspicion of the government, and now her every move her every word, is monitored carefully by the police.

Li Wenzu, meanwhile, is reunited with her husband, but their life has become a nightmare of oppression. Now marked by the government as traitors, they find themselves spied upon by their neighbors; at one point unknown women appear at their door, ready to cart their child away. Under the constant scrutiny and the loss of Wang’s career, their life seems nearly broken. Just as the Chinese Communist Party would have it for any and all who dare question their regime.

How is it possible Total Trust can film these people—earnest, hardworking citizens whose lives have been upended for their commitment to human rights—as they face the constant surveillance of the state and the unyielding scrutiny of their neighbors? Simply put, we are not to know. The film’s end credits simply list the cinematographers as “anonymous.” Those unknown, uncredited camera operators and other crew are every bit at risk as the film’s subjects. Jialing and her team communicated only through encrypted and media, fiercely protecting the anonymity of those who’ve put their lives at risk to tell this story. But their commitment has made for an intimate film, especially in its final act, when Chen and her son travel across the country to witness Chang’s trial only to be detained as they do so.

As devastating as these three women’s stories are—and they are devastating—perhaps even more so is the sobering fact that so many Chinese people have simply turned the other cheek, meekly accepting the government’s intrusion into their daily lives, even embracing it, turning against their neighbors and willingly reporting any activity they might deem “suspicious.” The program of surveillance would not work so well were it not for the submission to it by so many of China’s people. What’s most admirable about Jialing’s remarkable film is the fight these three women, their families, and, I hope, at least some others like them, are willing to put up in the face of adversity.

It would be nice to think that unchecked surveillance is a phenomenon limited to Communist China and its established program of social credit, but China is only the most compelling instance. Data compiled about each of us—from our social media clicks and feeds, our cameras and uploads, our public and private records—can all become part of a similar surveillance, especially in the encroaching age of artificial intelligence. Perhaps at this specific historical moment the problem is more pressing in China than anywhere else, but Total Trust should have you thinking: what does your government know about you? How would you respond if your or your spouse’s work conflicted with government policy? If your human rights were violated and your home and life the subject of constant surveillance?

Total Trust will ask that of you—of all of us—and the answers are not easy.

Total Trust opens theatrically in New York December 8, 2023, with other markets to follow. 97 minutes, in Chinese with English subtitles.