Musical genres had been evolving throughout the 1970s in a kind of a multicultural petri dish. Little more than a decade old, rock was splintering into arena rock, metal, and glam. Country-rockers plugged in and rocked out. Sensitive singer-songwriters became smooth yacht-rock crooners and street-savvy romanticists. Punks and new-wave ravers led a charge against all of them. But another musical idiom was gaining traction in the underground Black and gay clubs, where disco—bass-heavy and dance-oriented—found itself the subject of a spectacular rise in popularity. There was little middle ground with disco: you loved it or you hated it, and the hating is the subject of the new PBS documentary The War on Disco.

The 1977 film Saturday Night Fever, starring John Travolta and with its incredibly popular soundtrack, brought disco into the mainstream—in particular, to white, middle-class, mid-America—and helped make it, suddenly it seemed, ubiquitous. But once disco hit the mainstream, it faced a backlash, one explored in detail in The War on Disco, produced by Lisa Q. Wolfinger and Rushmore DeNooyer and premiering on Monday, October 30, 2023. Whether you were a hater or a player (or “a brother or a mother”)—and there were plenty of both—this savvy, short documentary examines the culture conflict as it reached its fever pitch one summer night in 1979, driven by racism, class angst, and homophobia.

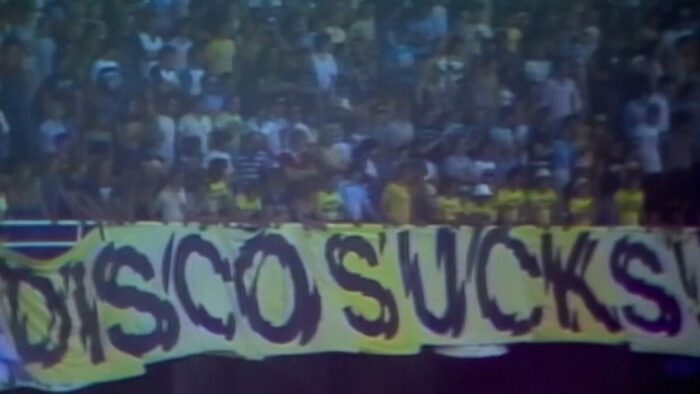

Of all places, the culture war literally exploded in flames on the supposedly elysian fields of a big-league baseball park. Baseball purists tout the game’s pastoral virtues, but on July 12, 1979, Comiskey Park’s field became the site of a riot. The southside team, the White Sox, were the second-worst team in baseball and desperate for a crowd. Rock-oriented Chicago DJ Steve Dahl had been fired from his gig at WDAI Radio when the station changed its format to the newly-popular disco and re-invented himself as an anti-disco scold at a local competitor, calling for what he called, only semi-seriously, “the eradication and elimination of the dreaded musical disease.” Dahl and White Sox promotion director Mike Veeck teamed up to host a “Disco Demolition Night” on Thursday, July 12, the price of admission just 98 cents and a disco record.

The gambit was simple: contribute your disco record and Dahl would blow them up between games of the twi-night doubleheader. Maybe that, Veeck figured, would bring some fans to the park. They expected maybe another 5,000 fans might show up. What neither Dahl nor Veeck had imagined was the the remarkable, pent-up hostility of the predominantly young, white, male crowd that came to Comiskey that night.

Fifty thousand showed up and paid admission. Another 20,000 reportedly milled about outside, unable to purchase a ticket. Dahl fulfilled his promise, exploding a container with the donated records in the outfield, leaving a fiery crater in its wake. And then it was mayhem: the crowd flooded the field, tearing up bases, destroying the batting cage, throwing albums like high-velocity, razor-thin frisbees. It took the police to clear the field; the Sox had to forfeit the second game to the only team with a worse record than their own, the visiting Detroit Tigers.

At the time, the event was lampooned in the media but hardly taken seriously. There were injuries but no deaths, arrests but no immediate consequence. The Sox finished out their homestand with three more home games against the Tigers over the weekend. July 12, 1979 remained a day of infamy for Major League Baseball but largely forgotten over time. What The War on Disco does do well is to frame that moment, and disco’s rise and fall generally, through the lens of race, class, and sex to show more precisely how the riot reflected a set of crises that were reaching a boiling point.

Rewatching the events of that night, it’s impossible not to notice that this was a crowd of thousands of (mostly) young white people rioting, burning, and destroying property, with nearly no law enforcement in sight. When black and brown people are beaten, killed, and arrested for far less nearly every day in this country, to see a largely unfettered, uncontrolled eruption of violence without reprisal is both amazing and appalling.

But then, to the young, white, and predominantly male audience Dahl spoke to with his anti-disco screeds, disco was indeed a threat. It was a musical idiom far more open to the talents of women than any Dahl and his ilk favored. It was black and urban, evolving from African folk and American dance. It was spectacularly and unambiguously gay in ways no hair-metal, punk, or country-rock band dared be, and even when it wasn’t, the men who frequented the clubs rivaled the women in their predilection for form-fitting polyester, gold jewelry, and dramatic makeup.

The War on Disco offers up what is a recognizable approach for the American Experience series, the Ken Burns-style participatory-expository documentary with careful explanations from expert observers and first-hand witnesses illustrating what archival documentation exists. Video footage from that night is surprisingly scant and poor in quality; it’s not like today when every event everywhere is documented by one or more witnesses with high-tech, high-quality camera phones on their persons. But The War on Disco employs this approach not because it’s traditional but because it works, focusing on a specific cultural moment that illustrates deeper fissures in American society.

Many of us did not recognize at the time just what the events of July 12, 1979 meant, nor how they would impact music in the decade to come. The film’s expert interviewees, like Ayana Contreras, host of “Reclaimed Soul” on WBEZ and contributor to Downbeat Magazine make clear. “The ultimate point was it was ‘the other’—that’s what they were rallying against—the people who were not like themselves.” Dahl may claim his actions were not racist, and it’s fair to say he may have had no explicit racist (nor homophobic, nor misogynist) intent; that does not mean the actions of the group did not reflect a palpable, if latent racism.

For many disco artists and stations, this was, simply, the beginning of the end: bookings and recording deals dried up quickly and nearly completely. “Comiskey Park was the moment that set the fuse,” says Felipe Rose of the iconic disco group The Village People (the group’s first recruit, he was the “Indian Chief” of the group as he was known in the day). “Suddenly, radio stations stopped playing disco music—not slowly, overnight.”

Other interviewees include Jefferson Cowie, Vanderbilt University Professor of History and author of Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class. “In the 1970s, an entire new front opened up in the battle over the culture. The Civil Rights movement, the women’s movement, the gay rights movement come along.”

And in The War on Disco, those movements find their cultural expression intersecting in the disco movement that enthralled many and enraged others, especially on that fateful night in July, 1979.

The War on Disco will broadcast on PBS stations at 9:00 pm EDT October 30, 2023 and stream for free through November 29, 2023, on all station-branded PBS platforms, including PBS.org and the PBS App, with closed captioning in English and Spanish.