“On-Screen, Off-Screen” is our monthly film series created to showcase a more personal retrospective about some of our favourite filmmakers. Each month, one 25YL staffer will choose one of their own favourite filmmakers – be it a director or performer or writer or composer or production designer, etc – and will analyse what it is about their on-screen work that they love, and how they’ve been influenced/inspired by them off-screen either personally or creatively or artistically. Maybe one of us will write about the entire filmography of a director, or someone might choose an actor associated with playing a certain role multiple times, or maybe there’s that one soundtrack by a composer that gets them every time. This month sees Lindsay Stamhuis reflecting on the early films of Richard Lester and how they inspired her in different ways at two different points in her life. Enjoy!

Story time!

The first time I saw a Richard Lester film I was about five years old, give or take. It was a rainy Saturday afternoon, which were usually Our Day with Dad each week because Mom worked as a bank teller part-time, and this often included Saturday shifts. My middle brother was two years younger than me (our youngest brother was not yet born) and so we were still of the right age for naptime. Not that there’s a wrong age for naptime, of course. In fact, I suspect my Dad put on the Spokane/Coeur d’Alene PBS station’s pledge drive programming that day to serve as background noise so that all of us, himself included, could while away a miserable afternoon with restorative slumber.

But it was not to be had, at least not by me. In the dreary post-meridiem hours, I sat transfixed by the warm black and white film broadcast into our living room. A Hard Day’s Night had me from the opening credits.

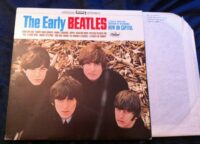

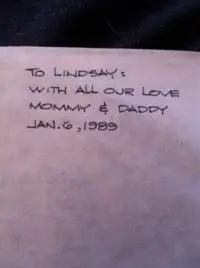

Now I was already a massive Beatles fan; thanks to my dad and his love of music, I was introduced to the Fabs at birth (or before, probably; not that my dad put headphones on my mother’s belly so I could listen in utero, but it wasn’t that far off…) and by the time I reached school-age, I was already able to recite facts about John, Paul, George, and Ringo, their hometown of Liverpool, and my favourite songs of theirs, much to the probable chagrin of the young people who would eventually become my friends. I owned books about The Beatles which I was too young to read; I owned vinyl records, even though I was too short and far too little to operate the record player; I had a crush on Paul McCartney, whose youthful face was all I knew about him even though, at the time I discovered him, he was in his mid-forties (to me, he was eternally twenty-something, frozen in time in the picture on my LP album covers). I was a mad second-generation Beatlemaniac. And there was nothing I could do to stop that.

My love for Dick Lester came through The Beatles, an organic offshoot of a love that chose me as much as I chose it. Sitting on the floor and watching The Beatles’ characters run and jump and sing and dance their way through less than 90 minutes of zany madcap adventures that one Saturday was enthralling, but it was the way the zaniness was captured that makes the film stand out in my mind, and which still enthralls me all these years later. That’s all down to Lester’s unique sensibilities, his sense of humour, and the way he was able to capture what made the Sixties such a magically surreal time in filmmaking.

(Side note: Dick Lester is either known for his collaboration with The Beatles or his work on the 1980s Superman films, and your appreciation of his work depends largely on which side of these opposing poles you fall closer to. For me, it was his work in the ’50s and ’60s that really spoke to me, for reasons that I’ve never quite analysed until now.)

Richard Lester was born in Philadelphia and moved to England as a young man, where he began making TV and short films, eventually catching the attention of Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan of The Goon Show. The Goon Show was a radio program broadcast on the BBC Home Service, consisting of surreal sketch comedy that would later go on to inspire the minds behind Monty Python, SCTV, and Kids in the Hall.

It’s really hard to imagine the kind of influence that these comedians had on austere, post-war Britain, and that might be a conversation for another column. Suffice it to say, Milligan and Sellers were looking for a way to translate their offbeat humour to television, and Dick Lester was the man they thought able to do it. With him, they produced three television series (The Idiot Weekly, Price 2d; A Show Called Fred; Son of Fred) and a one-reel comedy film, The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film (1959), which is about as sublime an example of surreal comedy as there is outside of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. This was the film that eventually led Messrs. Lennon/McCartney/Harrison/Starkey (all fans of The Goon Show, as was most of young Britain at the time) to enlist Lester to direct their first feature film.

A Hard Day’s Night (AHDN) is not a documentary, nor is it a mockumentary, but it’s not entirely a rockumentary either. And while Lester’s work with the Goons would go on to influence a world of absurd comedy, his work here with The Beatles made such a mark on everything from music television in the ’70s and ’80s to ’90s films like Spice World and That Thing You Do. The dialogue in AHDN was a stereotypical fictionalization of the way The Beatles actually talked, the storyline a stylized representation of how it must have felt to be a Beatle just before they made it big internationally. You’d hardly call it true-to-life, but it captures something essential about the experience of Beatlemania and Britain in the early-mid 1960s. The zaniness of The Goon Show films and TV shows makes its way into much of the film, which is filled with quick, witty banter (made doubly difficult to understand if you don’t speak Scouse, which Little Lindsay didn’t — though she learned eventually).

The film is shot outside, in the streets of Notting Hill and Marylebone or along the Thames outside London, which lends it a particular realism that was very hip at the time, appearing in everything from French New Wave to the “kitchen sink realism” popular in Britain. It makes the film feel immediate, and I struggle when people say it’s “dated” because it still feels as though it were happening now; in 2013, when I visited London for the first time and stole away for hours on end to visit these filming locations, I was struck by not just how little things had changed in places, but also how much the film had captured of the vibrancy and immediacy of its filming locations.

Richard Lester worked with The Beatles on their next film, Help!, though it is widely considered inferior to A Hard Day’s Night for many reasons — heavily fictionalized, far-fetched but not in a clever way (The Beatles themselves admitted that they filmed what they wanted to film based on where they wanted to go on vacation — Bermuda, the Alps, etc — so it hardly made for good storytelling; it probably didn’t help that they were stoned most of the time, either). At times the plot feels like poorly-written fan fiction, involving a sinister plot to sacrifice Ringo at the behest of a mystical eastern cult. But it is not without its charms — being the first film I’d ever seen of Lester’s that was also in colour, I was struck by the Sixties pop saturation, especially in the Beatles’ fictional homes (with their separate outside entrances that lead to one big living space within, differentiated by colour and texture specific to the interests of the characters — John has his books around him; George has earthy grass for a carpet, etc.) I think part of the fun for Lester must have been in working on a film that is so clearly not real life but is based on the public perception of real people. There’s something quirky and metafictional about it that I think a man like Dick Lester must have appreciated the chance to play with.

He also directed John Lennon in 1967’s How I Won the War, which is also an admirable film but hardly the stuff of legend — it’s a very black comedy about the misadventures of a fictional British WWII regiment stuck in North Africa, and was based on the novel of the same name. The various styles and ways of presenting the plot — breaking the fourth wall to have characters directly address the camera in one scene, while sending up the war film and docu-drama genres in another, for instance — go hand-in-hand with the experimental nature of film in that decade, speaking to the growing distrust of authority and anxiety over the state of global affairs as the Vietnam War swung into gear and mixing it with dark humour and struck in tones of absurdism that harken back to Lester’s early years with the Goons at times. But it didn’t go over well with critics and remains largely forgotten.

While he is probably most well-known for this work, his (arguably) greatest achievements are for other films. Filmed between the filming of A Hard Day’s Night but before its release catapulted both The Beatles and Lester to international stardom, The Knack …and How to Get it has earned a storied reputation in cinematic circles. Once again employing those techniques familiar to students of 1960s New Wave filmmaking, The Knack is seen as a wonderful example of what we now recognize as the Swinging Sixties. The film is about a young man named Colin (Michael Crawford) looking to sublet the third bedroom in his townhouse that he already shares with uber-cool womaniser Tolen (Ray Brooks), from whom he wants to learn “The Knack” — Colin possesses precisely zero skill when it comes to bedding the fairer sex, as it were, while Tolen has (at least in Colin’s mind) a veritable revolving door of beauties coming in and out of his room at all hours. Thus, when they meet Nancy (Rita Tushingham) soon after her arrival in London, all hell breaks loose as both Tolen and Colin set their sights on her.

It’s a ridiculous premise, but it’s the kind of surrealist fantasy that fits so well into both 1960s cinema and Lester’s oeuvre. Numerous moments come very close to breaking the fourth wall; fantasy sequences bookend one another — some in Colin’s classroom (he’s a school teacher), some in the stairwell of their home, some in the streets of London; Lester’s eye for interesting angles and camera views (with the help of cinematographer David Watkin) is especially noticeable in several scenes — I especially love the use of mirrors in tight scenes in order to show each actor’s faces with one wide shot. Lester uses it in the train car scenes in A Hard Day’s Night and in the stairwell in The Knack.

(The Bed Sitting Room is another fantastic example of what I love about Dick Lester. Based on a play by Spike Milligan and John Antrobus, the story concerns the aftermath of World War III — otherwise known as the “Great Misunderstanding” which lasted a whopping two minutes and twenty-eight seconds, including the signing of the peace treaty — and the strange mutations that have occurred in the survivors as a result, as well as the fact that, even in the aftermath of almost total annihilation, society reasserts itself in weird and wonderful and sometimes sad ways — people still waiting for the Tube, for instance. It’s bizarrely funny stuff. I prefer his older films to this one, but there is something so delicious about it, its subversiveness, its very evident Britishness, and the brilliant amount of fun being had, that I would be remiss if I didn’t mention it.)

Now that we’ve been acquainted with the 1960s work of Dick Lester, you must be wondering: Lindsay, what does this have to do with you?

Reader, I’ll tell you.

As a child and through my adolescence, I watched these fun and funny movies precisely because they were that: fun and funny. There was not much more to it than that. I developed and nurtured an appreciation for dry British wit and absurdist humour that I carry with me to this day, and I trace that directly back to my earliest introduction to Dick Lester’s comedies. And it was something I shared with my Dad, about the only person I knew until I met my husband who also enjoyed this style of comedy. But for a while — partly because of teenaged rebellion and it was the late ’90s so I had better, cooler things to do, things involving Discmans and bootlegged VHS copies of The Craft which are definitely a subject for another day — I turned my back on this world. It’s not an unheard of thing for a kid to do, I realise that. But for a good six years, while I tried on different personas, I lost touch with the things that would later give me such comfort.

But then, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 and before the anti-war sentiments over Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq engulfed my relatively sheltered world, I returned to the films of Dick Lester. I was in high school by then, a geeky kid in grade 11 who played flute in the band, sang in the jazz choir, writing fan fiction in my binder during English class. I’d been in what I later recognised was an emotionally abusive relationship, the kind of thing that stunts your growth while you’re in it before the b.s. it produces helps fertilise the soil at your feet so you blossom more beautifully when you finally get out of it. I didn’t properly acknowledge until later that, growing up when I did, I’d been privileged — with good education and high-quality Canadian health-care, with loving parents, largely free from the fears that I’d experience the kinds of Cold War-era anxieties that they had faced when they were my age. This is why I suspect the destabilisation of the early 2000s shifted my equilibrium so dramatically; for the first time in my life, nothing felt certain.

I rediscovered The Knack during the three weeks when all of our public school teachers went on strike. Something about the film re-sparked my interest in the 1960s — maybe it was Rita Tushingham’s geometric bob, or the patterns on the clothes of the women lined up outside of Tolen’s bedroom in Colin’s fever-dream, but I was hooked. I used my meagre earnings as a part-time retail sales associate to buy a mod-inspired wardrobe from vintage shops in the trendy, liberal neighbourhood where, 10 years later, I would buy my first home; I learned how to wing-tip my eyeliner and falsify my eyelashes, a la Twiggy and Catherine Deneuve, with Rimmel’s line of “London Look” makeup; I wore my hair like Françoise Hardy, swapped out my basic wire-rimmed reading glasses for black plastic cat’s eye frames. Mary Quant was my idol and Carnaby Street my place of worship. I suddenly felt at home in my body and at peace with my style for the first time…ever. And that meant a lot to me, especially then.

But it became so more than that.

Lester’s surreal comedic take on the world — especially in The Knack but also AHDN and Help!, which were comforting in the way they reminded me of being young and carefree at a time when nothing was carefree anymore — was the entry point to a world of humanistic sensibilities that suddenly made a hell of a lot more sense than anything else did at the time. A portal to the ethos that shaped a decade of protest and revolution. Yes, I found myself engrossed in the rich palettes of the idiosyncratic world of ’60s fashion (geometric patterns, Day-Glo colours, vintage synthetics and organic cotton), but it wasn’t long before I was listening to the protest songs of ’60s troubadour poets like Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, and Bob Dylan, and reading the books and essays of ’60s luminaries and philosophers — Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test is still one of my all-time favourite books. I brought my guitar to school, and in a nice circular completion, the first song I ever learned was “Blackbird”, a song that my perennial fave Paul McCartney wrote in solidarity with the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. Along with the cultural indicators of that bygone time that I literally wrapped myself in during the day — its clothing and visual aesthetic — the moral fibre of 40 years ago fused itself to my own, ossifying until it was no less a part of me than the bones I was born with.

How ridiculous it might seem to you that the absurdist comedy films from a director working 60 years ago could cause a girl to solidify her personal philosophy; I’ve just written 3000 words about it and I’m still not even sure I’m adequately prepared to explain how it happened. It’s just one of those things. Dick Lester’s 1960s films were a gateway drug to an ethos that I still carry with me to this day; I can’t watch one of his Sixties films today without feeling like I’m 17 all over again, finding my voice for the first time. And they couldn’t have done that if they hadn’t hooked me with “fun and funny” to begin with, way back on that blustery Saturday in 1990.

Don’t know how I stumbled on your essay / article here , and I’m having a better day for it . I can’t imagine how old you are ? With that said I believe you expressed the feeling of many baby boomers such as myself . Indeed , watching a Hard Days Night harkens people back to a time where the world was more civilized, organic to the root , and innocence long lost — technology has much to do with this — You mentioned “The Knack “ as being a period piece film, now I must find it somewhere . “ How I Won The War “ I haven’t seen since it was released in the sixties . As most of my close friends in Upstate New York were Communists in the later part of the sixties , I believe it may prove interesting to revisit the film now . I don’t even remember the breaking of the fourth wall in respect to giving a nod to the tragedies of Viet Nam at the time . As you appear to be well informed, do you believe the film would be timely to watch today apres a fifty year respite ?

I’m in San Francisco, I can relate to the blustery weather on a Saturday afternoon . There is no time like the present …

With Regards ,

Jakob Gerber